I read the news today - oh,oh - and I came across a pair of obituaries.

They told the lives of two extraordinary-sounding men who figured large in the touchstone events of recently past American history: Vietnam and Watergate.

First, the warrior:

David Hackworth

Unorthodox Vietnam commander immortalised in Apocalypse Now

Michael Carlson

Monday May 9, 2005

In June 1971, Colonel David Hackworth, probably America's most decorated soldier in Vietnam, appeared on ABC television and told his countrymen that the war could not be won, that US military leaders had failed to understand or train their men for the nature of the country or the conflict, that Saigon would fall to the communists within five years and that one of every five American casualties had been the victim of so-called friendly fire.

This criticism put Hackworth, who has died of cancer aged 73, under concerted attack from his superiors, an assault made easier to sustain by the fast and loose approach to regulations he had employed as commander of a Blackhawk air cavalry brigade in Vietnam. His troops wore US civil war hats, and Hackworth, as commander of the unit, later became the model for Colonel Kilgore, the abrasive, cigar-chomping officer played by Robert Duvall in the 1979 film Apocalypse Now. Hackworth had set up his unit's own bordello in Vietnam, and the US army used that and other violations to threaten him with court-martial. However, General Creighton Abrams, the overall commander in Vietnam, called him "the best battalion commander I ever saw", and, in 1971, he was allowed to resign with an honourable discharge. He threw away his medals in protest, and moved to Australia.

In the 1980s, Hackworth returned to the US after his medals were reissued, and his book about Vietnam, About Face, became a best-seller. From 1990 to 1996, he was a contributing editor on defence at Newsweek magazine, where, in 1996, he wrote a column revealing that Admiral Michael Boorda, a former chief of US naval operations, wore combat medals he had not earned.

When the admiral committed suicide, Hackworth again incurred the military's wrath. He was accused of lying when he claimed to be the army's "most-decorated soldier" - the US keeps no statistics on such matters - and of wearing an unearned Ranger tab. An army investigation found that Hackworth had been issued the tag in error, but had never been given a number of medals he had earned. His decorations included two distinguished service crosses, the second highest US award for valour, 10 silver stars, eight bronze stars and eight purple hearts.

After leaving Newsweek, Hackworth wrote a syndicated newspaper column, Defending America, with his third wife, Eilhys England. Covering both Iraq wars and peacekeeping actions in Somalia, the Balkans and Haiti, he became a fierce critic of the US establishment. His website, Soldiers For Truth, lambasted the Pentagon's "perfumed princes", whom he claimed constantly betrayed the ordinary solider. He was particularly incensed that Donald Rumsfeld used a machine to sign condolence letters sent to the families of dead soldiers in Iraq.

Hackworth's army connections began young. Orphaned at five months, and raised by his grandmother in Santa Monica, California, he shined shoes at a local army base, becoming a mascot to the soldiers, who gave him his own uniform. At 14, he lied about his age and joined the US merchant marine; a year later, he paid a sailor to impersonate his father and get him into the army, where he served in postwar Italy, policing the border dispute over Trieste.

He won his first silver Star in Korea at the age of 20, when his battlefield commission made him the army's youngest captain. Commanding the Wolfhound Raiders, he led one attack despite being shot in the head, modelling himself on General James Gavin, America's youngest second world war general (played by Ryan O'Neal in the 1977 film, A Bridge Too Far).

Hackworth volunteered for service with the US special forces in Vietnam, and, as the army's youngest full colonel, returned in 1965, commanding a paratroop unit. With General SLA "Slam" Marshall, he wrote the Vietnam Primer, a guide to counter-guerrilla tactics. He used his theories about the enemy, whom he referred to as "the G", to transform a hapless 4/39 infantry unit into what became known as the Hardcore Battalion, driving his men so hard they allegedly put a cash bounty on him.

But he also won their loyalty, by such acts as leading the rescue of a trapped company while riding on the strut of a helicopter. It was one of three times on which Hackworth was nominated for the congressional medal of honour, America's highest award.

After leaving the army, he was successful in property and restaurants in Brisbane, and became active in the Australian peace movement. He returned to Greenwich, Connecticut, in the 1980s.

Hackworth's many books included a novel, Price Of Honor, a volume of war dispatches, Hazardous Duty, and a memoir of the hardcore battalion, Steel My Soldier's Hearts. Serving soldiers fed his website with information about the army's leadership shortcomings. Last February, he wrote, "Most combat vets pick their fights carefully. They look at their scars, remember the madness and are always mindful of the fallout ... the White House and the Pentagon are run by civilians who have never sweated it out on a battlefield."

Hackworth died in Tijuana, Mexico, while pursuing alternative treatments for bladder cancer, a common cause of death among soldiers exposed to the dioxins Agent Orange and Agent Blue, used to defoliate Vietnam.

He is survived by Eihlys and his stepdaughter, two daughters and a son from his first marriage, and a son from his second marriage.

· David Haskell Hackworth, soldier, born November 11 1931; died May 4 2005

Second, the politician:

Peter Rodino

US congressman whose fastidious chairmanship of the impeachment committee helped bring down Richard Nixon

Harold Jackson

Monday May 9, 2005

As chairman of the US house judiciary committee, Peter Rodino, who has died aged 95, presided over the 1974 impeachment proceedings against President Richard Nixon, who was accused of illegally trying to cover up the burglary of the Democrats' Watergate election headquarters. Rodino's impeccable conduct of the highly charged hearings brought this little-known Democrat congressman from New Jersey a respectable niche in America's political pantheon. The overwhelming demand for the president's impeachment came in October 1973, in the wake of his infamous Saturday night massacre. Nixon ordered the dismissal of Archibald Cox, the special prosecutor investigating the Watergate break-in, after Cox subpoenaed secret tapes of the president's Oval Office conversations, which the White House refused to hand over.

The US attorney general refused to carry out the presidential order to sack Cox, and was himself fired. His deputy then refused, and was also sacked. Finally, an acting attorney general was sworn in, and the deed was done. By the following day, the House of Representatives registered 22 impeachment motions, and the speaker proposed selecting a special committee of leading congressmen to consider the charges. Rodino, a stickler for procedure, argued that his judiciary committee already existed to deal with the issue, and he was supported by the powerful Democrat majority leader, Tip O'Neill.

As it turned out, Rodino's shrewdest move was to recruit a Republican lawyer, John Doar, to head the investigation - the two men reinforced each other's belief that it was vital for public confidence to eschew partisanship, maintain a strictly judicious approach, and build a mountain of irrefutable evidence. With that in mind, they set about reviewing the vast body of legal precedent (going back to colonial days) and the mass of paper already accumulated by the senate's Watergate investigation.

When the hearings opened in May 1974, the committee had 21 Democrat and 17 Republican members. It was a potentially explosive political mix, but Rodino managed to sustain a calm and judicial air, courteously reining in attempts to score party points. Rivetted by the daily television coverage, Americans quickly signalled their approval of Rodino's slow, but inexorable assembly of the evidence, a factor which undoubtedly played a significant part in the outcome.

Committee members had to vote on five articles of impeachment, and there was a wide expectation that there would be a straight party split. That happened on two of the lesser counts, but a majority of the Republican members came out in support of the three main charges - obstructing justice, abuse of power and withholding evidence. It was a clear response to the pile of carefully assembled evidence and the discipline that Rodino had imposed on the hearings.

The vote was dramatically justified three days later when a new federal disclosure order revealed the existence of a recording of a key conversation in the Oval Office on June 23 1973, six days after the Watergate break-in. It showed that Nixon had ordered the CIA to obstruct all the investigations being carried out by the FBI, a multiple breach of his oath of office. Dissident Republicans on Rodino's committee immediately switched their votes to make the impeachment recommendation unanimous, and Nixon became the first US president to be forced out of office.

Rodino took no pleasure in the outcome; he said later that he had been praying that his committee would be able to exonerate Nixon. He was, however, outraged by President Gerald Ford's decision to issue a blanket pardon to his predecessor. "When I heard that I almost went bananas," Rodino said in 1992. "Ford had just misread the whole thing."

The son of an immigrant Italian carpenter, Rodino grew up in a poor district of Newark, New Jersey. In the classic tradition of second-generation US immigrants, he pulled himself up by his bootstraps. To help recover his speech, badly affected by a childhood bout of diphtheria, he spent hours reciting Shakespeare through a mouth full of marbles. As an adult, he endured 10 years of menial jobs while studying at night for a law degree.

When he achieved it, at the age of 28, he joined a local law firm and became immersed in politics, running unsuccessfully for the New Jersey state assembly. He served in north Africa and Italy during the second world war, and was demobilised as a captain.

After the war, he renewed his political ambitions, securing a congressional seat in 1948. He was subsequently re-elected for 19 terms, during which he showed steady dedication to civil rights reform. He became one of the main congressional sponsors of President Lyndon Johnson's landmark legislation of 1966, and finally retired in 1988.

Rodino's first wife, Marianna, died in 1980. He is survived by his second wife, Joy, and by a son and daughter.

· Peter Wallace Rodino, politician, born June 7 1909; died May 7 2005

These two men, in their own ways, encapsulated a kind of American spirit we all know, or used to know. One, the politician, was a poor immigrant's son who pulled himself up, taught himself, worked hard, served loyally and lived out a kind of classic version of the American dream - he became a successful politician who found himself managing the impeachment of a criminal president and doing so with honour, dignity and scrupulous care. The other was a military hero - a classic maverick hellraiser. The kind a man who wore Confederate uniforms and clung to helicopter struts as they flew into battle. The kind of figure who appears in movies and indeed he did - played by Robert Duval in Apocalypse Now.

You may argue with their views, but you can't argue with their sense of duty. To their own values and those of the communities they served: the military, the body politic.

And both these men really do have mythic - as in the 20th century American mythic - qualities. One seems to have stepped out of a Frank Capra, a Preminger or an Elia Kazan film, the other from Fuller, Peckinpah or Siegal. These were the kinds of characters and stories that struck me strongly growing up. They inspired that fascination with the American myths and fables, cinema, books that was the defining cultural flow of the 20th century.

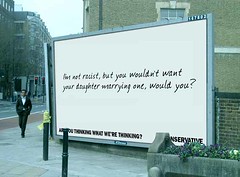

But when I read about their lives, I also get a feeling of sadness. A sense that that cultural flow that bore them is starting to dry up, switch currents. When I compare their struggles with the people who now govern America - I can feel the shift, the emptiness that lays there.

America as a country seems to be changing. And in the future that's coming around the corner, it will need the spirit of men like Rodino and Hackworth who bravely, relentlessly, often at thier own risk, protected those institutions that were their life.